13 Hypothesis Testing

13.1 Significance Tests

Confidence intervals are one of the two most common types of statistical inference. Use a confidence interval when your goal is to estimate a population parameter. The second common type of inference, called significance tests, has a different goal: to assess the evidence provided by data about some claim concerning a population.

A significance test is a formal procedure for comparing observed data with a claim (also called a hypothesis) whose truth we want to assess. The claim is a statement about a parameter, like the population proportion \(p\) or the population mean \(\mu\). We express the results of a significance test in terms of a probability that measures how well the data and the claim agree.

13.1.1 Hypotheses

A significance test starts with a careful statement of the claims we want to compare.

- \(H_0\): The claim we weigh evidence against in a statistical test is called the null hypothesis. Often the null hypothesis is a statement of “no difference.”

- In any significance test, the null hypothesis has the form:

\[H_0 : \text{parameter} = \text{null value} \]

- \(H_a\): The claim about the population that we are trying to find evidence for is the alternative hypothesis.

- The alternative hypothesis has one of the forms:

\[ \begin{aligned} H_0 &: \text{parameter} > \text{null value}\\ H_0 &: \text{parameter} < \text{null value}\\ H_0 &: \text{parameter} \not = \text{null value} \end{aligned} \]

To determine the correct form of \(H_a\), read the problem carefully.

The alternative hypothesis is one-sided if it states that a parameter is larger than the null hypothesis value or if it states that the parameter is smaller than the null value.

It is two-sided if it states that the parameter is different from the null hypothesis value (it could be either larger or smaller).

- The hypotheses should express the hopes or suspicions we have before we see the data. It is cheating to look at the data first and then frame hypotheses to fit what the data show (i.e. “p-hacking”).

- Hypotheses always refer to a population, not to a sample. Be sure to state \(H_0\) and \(H_a\) in terms of population parameters.

- It is never correct to write a hypothesis about a sample statistic, such as \(\hat p=0.64\) or \(\bar x=85\).

13.1.2 Interpreting P-values

The null hypothesis \(H_0\) states the claim that we are seeking evidence against. The probability that measures the strength of the evidence against a null hypothesis is called a P-value. The probability, computed assuming \(H_0\) is true, that the statistic would take a value as extreme or more extreme than the one actually observed is called the P-value of the test. Small P-values are evidence against \(H_0\) because they say that the observed result is unlikely to occur when \(H_0\) is true. Large P-values fail to give convincing evidence against \(H_0\) because they say that the observed result is likely to occur by chance when \(H_0\) is true.

13.1.3 Drawing a Conclusion

The final step in performing a significance test is to draw a conclusion about the competing claims you were testing. We make one of two decisions based on the strength of the evidence against the null hypothesis (and in favor of the alternative hypothesis):

\[\text{reject } H_0 \text{ or fail to reject } H_0\]

Note: A fail-to-reject \(H_0\) decision in a significance test doesn’t mean that \(H_0\) is true. For that reason, you should never “accept \(H_0\)” or use language implying that you believe \(H_0\) is true.

There is no rule for how small a P-value we should require in order to reject \(H_0\). But we can compare the P-value with a fixed value that we regard as decisive, called the significance level. We write it as \(\alpha\), the Greek letter alpha.

If the P-value is smaller than alpha, we say that the data are [statistically significant][Statistical Significance] at the level . In that case, we reject the null hypothesis \(H_0\) and conclude that there is convincing evidence in favor of the alternative hypothesis \(H_a\).

In a nutshell, our conclusion in a significance test comes down to

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{P-value} &< \alpha \rightarrow \text{reject } H_0 \rightarrow \text{convincing evidence for } H_a \\ \text{P-value} &\geq \alpha \rightarrow\text{fail to reject } H_0 \rightarrow \text{not convincing evidence for } H_a \end{aligned} \]

13.1.4 Example

(From “Is this gender discrimination” CYU)\ Factinate.com claims that 84% of teenagers think highly of their mother. To investigate this claim, a school psychologist selects a random sample of 150 teenagers and finds that 135 think highly of their mother. Do these data provide convincing evidence that the true proportion of teens who think highly of their mother is greater than 0.84?

- State appropriate hypotheses for performing a significance test. Be sure to define the parameter of interest.

Let \(p =\) the proportion of teenagers who think highly of their mother.

\(H_0: p = 0.85\) (This is because we are assuming there is “no difference” from Factinate.com’s claim)

\(H_0: p > 0.85\) (The evidence that we got is \(\frac{135}{150}\), which is greater than 0.85; also the problem asks, “Do these data provide convincing evidence that the true proportion of teens who think highly of their mother is greater than 0.84?”)

- The school psychologist performed the significance test and obtained a P-value of 0.0225. Interpret the P-value.

Assuming that that \(H_0\) is true (i.e. \(p = 0.84\)), there is a 0.0225 probability of getting a sample proportion of \(\frac{135}{150}\) or greater purely by chance.

* You can also include the context as we have before, but the context in this answer already infers knowledge that we are interpreting in the context of long-term frequency. This is really all you need for this interpretation.

- What conclusion would you make at the \(\alpha = 0.05\) level?

Since \(\text{p-value } = 0.0225<0.05=\alpha\), we reject the null hypothesis that the proportion of teenagers who think highly of their mother is 0.85. There is convincing evidence that the true proportion of teens who think highly of their mother is greater than 0.84.

13.2 Type I and II Error

When we draw a conclusion from a significance test, we hope our conclusion will be correct. But sometimes it will be wrong. There are two types of mistakes we can make.

If we reject \(H_0\) when \(H_a\) is true, we have committed a Type I error.

If we fail to reject \(H_0\) when \(H_a\) is true, we have committed a Type II error.

We can sum this up with this up with this table:

| Truth about the population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| \(H_0\) is true | \(H_0\) is false | ||

|

Conclusion based on the sample |

Reject \(H_0\) | Type I Error | |

| Fail to reject \(H_0\) | Type II Error | ||

When considering the consequences of the results of an inference task, we want to consider Type I and II errors. In some cases, we’d prefer to have Type I errors over Type II. In other instances, it’s the opposite.

13.2.1 Type I Error

The probability of a Type I Error is \(\alpha\) \[P(\text{Type I Error})=\alpha\]

13.2.2 Type II Errors and Power

A significance test makes a Type II error when it fails to reject a null hypothesis \(H_0\) that really is false. There are many values of the parameter that make the alternative hypothesis \(H_a\) true, so we concentrate on one value. The probability of making a Type II error depends on several factors, including the actual value of the parameter. A high probability of Type II error for a specific alternative parameter value means that the test is not sensitive enough to usually detect that alternative.

The power of a test against a specific alternative is the probability that the test will reject \(H_0\) at a chosen significance level when the specified alternative value of the parameter is true.

The significance level of a test is the probability of reaching the wrong conclusion when the null hypothesis is true.

The power of a test to detect a specific alternative is the probability of reaching the right conclusion when that alternative is true.

The power of a test against any alternative is 1 minus the probability of a Type II error for that alternative; that is, \(power = 1-\beta\), where is the probability of making a Type II error.

\[ \begin{aligned} P(\text{Type II Error}) &= \beta \\ P(\text{Type II Error}) &= 1 - \text{power} \\ \text{power} &= 1 - \beta \end{aligned} \]

* Keep in mind that you are not expected to know how to calculate power or \(\beta\) without one of the other. i.e. you will always be given the power or \(\beta\) in a problem.

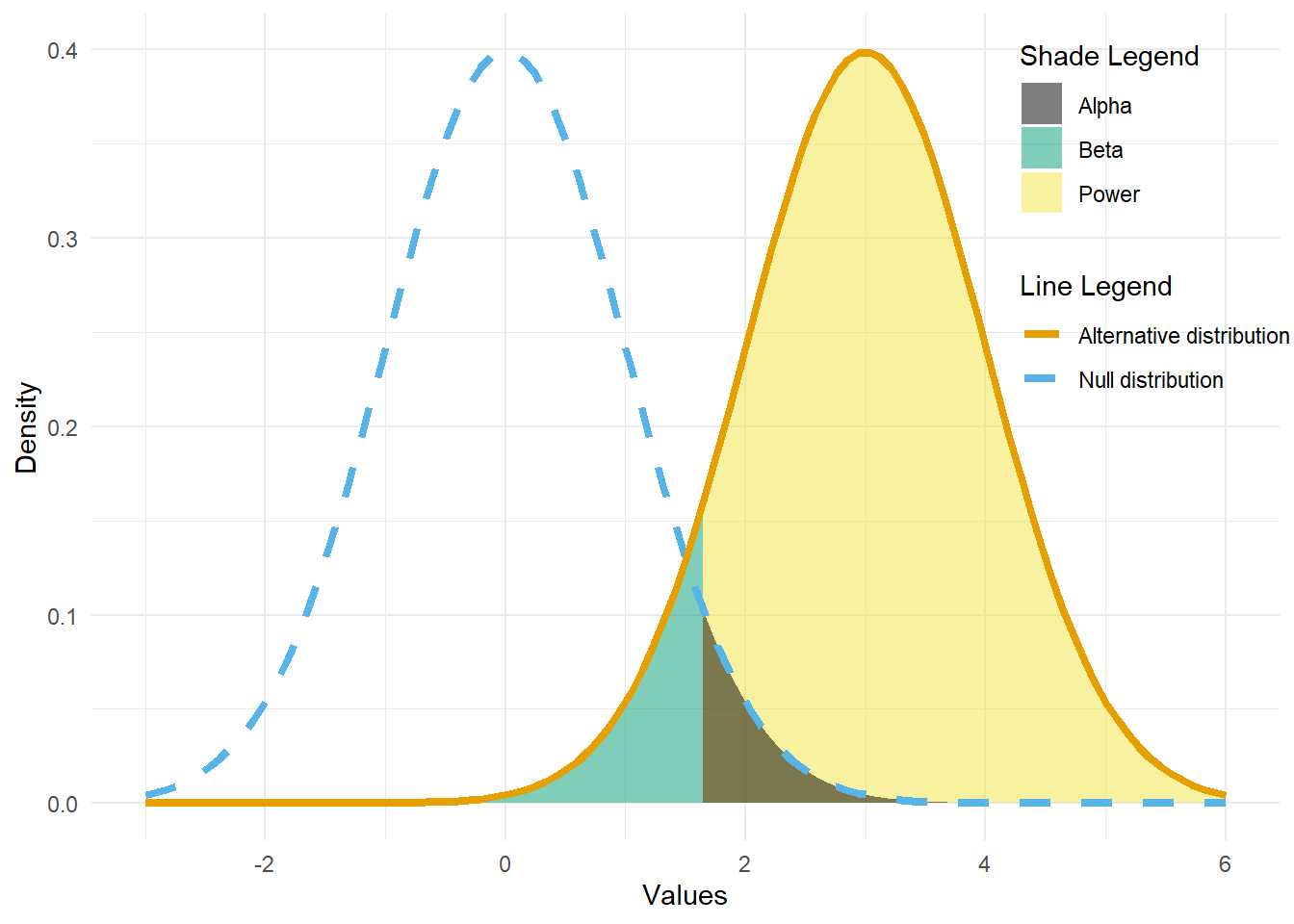

How power looks like

This diagram illustrates how we can visualize power in a one-sided test checking to see if a parameter is larger than the null parameter. The null parameter here is 0 and the alternative parameter is 3. Each of their respective distributions are centered at 0 and 3. To think about power, first we look at the \(\alpha\) value, which gives us the rejection region (shaded in black) in which any statistic that we get there will reject the null hypothesis.

Power is the probability that we reject the null hypothesis given that the alternative parameter is actually true. So, power is represented in the yellow area, which starts at the same x (our “cut-off” value for rejection based off alpha) that the rejection region starts.

\(\beta\) is the probability of Type II error, where we do not reject the null hypothesis when it is actually wrong. So it is represented in the green area.